#equity

Black History Month: Facing Inequities and Committing to Solutions

By Luis Borrero

This month, we celebrate Black History and recognize the lived adversity and accomplishments of those in the Black community. From Martin Luther King Jr. to Warren Washington, Black leaders have had an immeasurable impact on American history. While we honor the work of many distinguished African Americans, we also acknowledge that the struggle for racial justice and equity is far from over. One area in particular that this struggle impacts is the climate crisis.

Climate change and all of its effects – increased heating, pollution, health degradation, etc. – are not uniformly felt by everyone, and they never have been. Historically, Black people are more likely to breathe in polluted air, live in flood-prone areas, and reside near toxic sites. From freed slaves being given land that would eventually be surrounded by petrochemical plants, to redlining and discriminatory housing policies, the historical injustices continue to have an impact on the Black communities. Due to certain actions like the discriminatory housing policies, predominantly Black neighborhoods often have more pavement and concrete, fewer trees, and higher average temperatures. These “developed” neighborhoods can get up to 27 °F hotter than most rural areas. Having grown up in an inner city poor neighborhood, I know exactly how this feels.

Reading, Pennsylvania has been consistently ranked among the poorest cities in all of America. It’s hard to find a neighborhood that hasn’t been plagued with abandoned buildings and dilapidated infrastructure. I grew up in a row home in Reading. In the middle of the city, this townhouse had rugged bricks patterned all over the front lawn. Adjacent to this row home, with its sturdy roots bulging out from under the bright red bricks, was a tree. I remember being fascinated by this oasis of nature that was thriving in my cement jungle. Greenery wasn’t something that many of us were exposed to. Sometimes, if we were lucky, flowers would grow through the concrete cracks. Even now, whenever I come across a dandelion, I can still hear my cousins shouting at one another, “Don’t step on it!” and asking “How big will it get?”

As a child, I thought this was the standard for everyone. When I would visit my favorite teacher, Ms. Fasiq, I noticed there was much more of, well, everything at her house. Ms. Fasiq was a short, pale-skinned woman with large, circular glasses. She was a kind woman who invited us to her home to meet her family. Healthy and freshly trimmed grass adorned her front lawn and her backyard. There were trees, flowers, and open space everywhere. This vastly different place, this region bustling with nature and freedom, was in Reading, Pennsylvania. It took until adulthood to get educated enough and realize that there’s a problem. For every problem, though, there’s a solution. As a Black youth, I was, and still am, an instrumental part of the solution.

The challenges the Black community faces in the climate crisis are clear, and many similar unfair burdens are also carried by the youth. Youth are also on the front lines of the climate crisis, facing the consequences of years of neglect and an uncertain future. Black youth sit at the crossroads of these two groups and feel the weight of climate injustices in a distinct way.

So, how do we get more black youth involved in the climate movement?

Well, there isn’t one simple answer. There are many Black youth activists making an impact in their community, but there could be- and should be – many more. Often times, like in my case, youth don’t realize or can’t articulate the problems they’re facing, or they have other more seemingly immediate priorities. Other times their concerns are dismissed or ignored. Many, like myself, start to seek solutions in the work that Black leaders have already begun. Many Black leaders, like Harold Brooks, have spent a lifetime facing the consequences of the climate crisis.

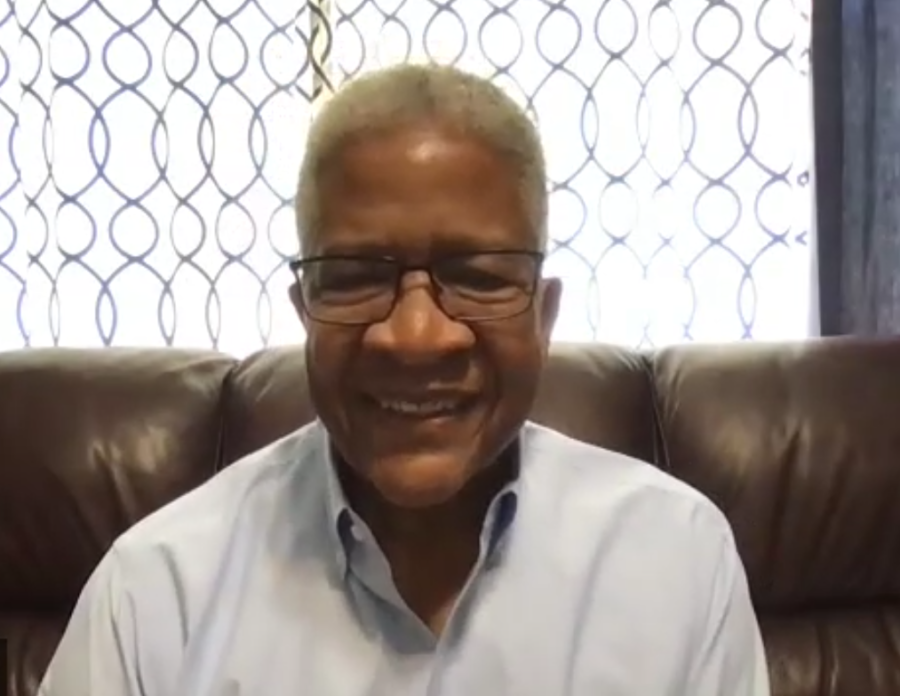

A Los Angeles native, Harold Brooks grew up experiencing the repercussions of climate change firsthand. As a child in elementary school, Brooks and his classmates would be ushered into the building after smog alerts would sound while they were playing outside. “The smog was so dense in Los Angeles,” Brooks explains, “that the sky would be kind of a yellowish-grayish color.” Brooks thought that the persistent burning in his lungs that he and others felt when playing outside was normal. This experience eventually led Brooks to begin working in the climate space. Since then, he has served over 40 years as an executive with the American Red Cross, and is currently the Chief Resilience Officer at the Global Community Resilience Institute and sits on TCI’s Board of Directors.

“The more education, the more thoughtful ways that we can get these messages, get this information into the hands of Black youth.”

While Brooks was able to dedicate time and energy towards disaster relief and climate-related issues at a relatively young age, not all Black youth have the same opportunity. “When you put together your hierarchy of needs and concerns,” Brooks pointed out, “often there are so many things that seem to be more in the face of the black youth, particularly in the inner cities, that they don’t stop to think about the continuum that includes climate and climate change.” With plenty of other hardships in the way, the climate crisis can often take a backseat. One of the ways we can try to combat this situation is through education.

“The more education, the more thoughtful ways that we can get these messages, get this information into the hands of Black youth,” Brooks assured me. This reasoning, education being a pathway to climate solutions, is why Brooks is a supporter of The Climate Initiative.

With our TCI Learning Lab modules, we’ve been able to reach students in over 27 states with easily accessible climate education. Soon, we’ll be launching a new module titled, “Climate Justice & Equity” that will dive into many of the issues discussed here. TCI strives to make an impact in other areas as well. Up to 60% of our grants are reserved for funding initiatives by Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). As TCI continues to grow, we’ll continue to try and find new ways to ensure a future that’s just and equitable for all.

Much like Harold Brooks, my experiences have led me to dedicating my time to the climate crisis. I, along with others, have been able to use my skill and passion to make a difference with The Climate Initiative. Whether you’re an adult with no climate experience, or a youth trying to find their way in the climate space, there is always room for more voices. Whatever your passion may be, we can use it to keep pushing the movement forward.

We know the climate crisis is a daunting challenge, and it’s going to take all of us to get through it. It’s important, Brooks emphasizes, to “stay the course and know that the day that we put in of moving the boulder up the hill is another good day and we’ll get more and more hands to help us. And suddenly, it’s not the problem or the challenge that we thought it was. We’ve got to all figure out a way to listen to and learn from the youth.”

That we do.