#equity

For Black History Month and Beyond: Including Marginalized Communities in the Climate Conversation

By Jono Anzalone

Black communities are disproportionately affected by climate change due to lingering discrimination, but we all have the power to change this.

This Black History Month and beyond, it’s important to not only reflect on the contributions the black community has made to our society, but recognize the hardships they still face. The effects of climate change impact BIPOC communities the most, yet their voices are muffled underneath the residual weight of systemic racism and economic injustice. It’s no coincidence that African Americans are 75 percent more likely to live in neighborhoods that border pollutive industrial facilities; or that black communities are 40 percent more likely to reside in areas exposed to extreme weather events and temperatures.

For too long, environmentalism in climate action has been a place where not all individuals have felt welcome or a sense of belonging. When communities are faced with extreme food and housing insecurity, among other pressing social issues, being able to take a step back and examine the climate crisis may seem like a privileged opportunity. But if we wish to save our shared home, we need to address this inequity.

Recognizing Climate Inequity

Growing up in Nebraska, a state with little racial diversity where less than 6% of the population is black, I had very little insight into the issues that were impacting many of our brothers and sisters across the United States. It wasn’t until I started responding to natural disasters that I saw how marginalized communities were bearing the brunt of climate-related issues.

The truth of the matter is federal and state programs have not always had black interests in mind. The repercussions of pervasive redlining and racially-based economic regulations continue to trickle down and further exacerbate hindrances black families are facing as the global temperature rises and weather intensifies.

For instance, a 2018 study conducted by Rice University and the University of Pittsburgh shows that minorities often experience a wealth decrease after a natural disaster while their white neighbors receive a surplus in federal financial assistance. This means that while white, well-endowed subdivisions find themselves bouncing back quickly, lower-income communities of color are left struggling with profound infrastructure issues, expensive insurance policies, and little money to help them recover.

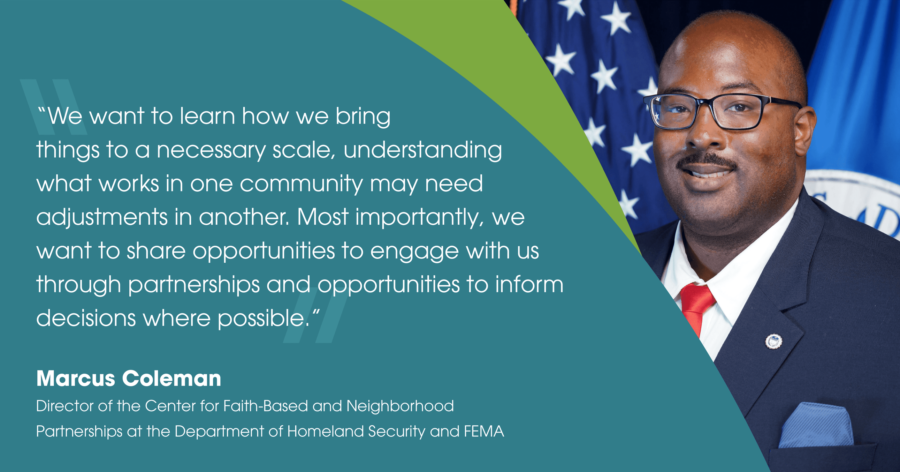

Marcus Coleman and his team, however, are working to close this gap.

Coleman is the Director of the Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships at the Department of Homeland Security and FEMA. Speaking with Marcus about climate equity for Black History Month, he emphasized the importance of elevating black voices in order to properly respond to their challenges.

“I think a lot of lessons were learned from Katrina — one of those being we needed to really strengthen our coordination, collaboration, communication, and cooperation with faith and community groups before, during, and after disasters,” Coleman said. “Many people may not know that FEMA has a civil rights division that’s committed to identifying and providing recommendations to address perceived and experienced violations of civil rights, and to really be thoughtful about how we can be more equitable in our support and work of disaster survivors.”

Although it certainly helps, distributing more money or working hands to help reconstruct and rebuild the homes of black community members won’t address the causes of these repetitive damages. Overcoming these challenges requires us to look at the intersectionality of these hurdles in order to entirely remove them, not just jump over them.

To start, we can heed Director Coleman’s advice and open an honest and accessible forum for underserved populations where they can divulge how climate change is truly affecting them.

“My posture for my office and our posture as an agency is to listen, to learn, and to share,” Coleman said. “We want to listen to the needs and concerns and the great things that are already happening and amplify those. We want to learn how we bring things to a necessary scale, understanding that things that work in one community may need some major adjustments in another. And most importantly, we want to share the opportunities to engage with us as an agency through partnerships and opportunities to inform decisions where possible.”

The climate conversation is currently spearheaded by youth advocates, generous philanthropists, and environmental leaders — but a considerable number of these individuals come from a comfortable economic and social background that grants them the time and energy to push for a healthier environment. Meanwhile, for a substantial portion of the black population, time and energy are devoted to surviving on a day-to-day basis. The U.S. Census Bureau found that in 2019, the poverty rate among the black population was 18.8 percent, and while blacks represented 13.2 percent of the total U.S. population, 23.8 percent of the poverty population was comprised of black communities.

We cannot expect to work together to solve the climate crisis if many of our neighbors find environmentalism to be a luxury, because ultimately, the deterrents they’re facing also hurt all of us.

Adding Black Voices to Climate Discourses

One meaningful part of celebrating Black History Month is finding ways to uplift the community to prevent such crises from continuing. Each and every one of us can read an article, take time to dive further into ongoing concerns, or simply reach out to our black neighbors and listen to what troubles them the most.

As Director Coleman puts it, “We have to lead with humility to build community.” I find his three-step approach helpful in initiating these important conversations:

- Be mindful of the lens through which you view climate-related disasters. Each situation is unique; treat possible recovery solutions that way.

- Invest in partnerships that can help build climate resilience in areas still suffering from systemic deadlocks.

- Allocate the resources, whether it be financial, educational, or even emotional, to those who battle the multifaceted effects of climate change on a frequent basis.

Understanding the cross-sectionality of climate change — that it’s not just an environmental issue — is key. But many people are stuck categorizing climate change this way.

He also mentioned how in the past, there’s been an under-investment in hazard mitigation from government entities, from “inconsistent building codes” to a lack of guidance on preparing for sea-level rise.

In one case study, FEMA responded by partnering with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Kentucky to develop a personalized heat wave mitigation plan through collaborative meetings, informational booths, questionnaires, workshops, and more with local community members. With such diverse input, homes were appropriately fortified in vulnerable populations to protect them from extreme heat.

There’s more work to be done, but it’s vital that we also highlight what is currently being accomplished by black trailblazers in the climate/humanitarian field. Director Coleman and I personally want to celebrate and thank the following individuals for inspiring us and others on the climate front:

- Shalanda Baker, Deputy Director for Energy Justice, former Professor of Law, Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University, and author of Revolutionary Power: An Activist’s Guide to the Energy Transition

- Harold Brooks, Chief Resilience Officer at the Global Community Resilience Institute, Board Member for The Climate Initiative and former Career Humanitarian at the Red Cross, Africare, and the Peace Corps

- Krystal Williams, Founder of the Portland-based law and business advisory Providentia Group, and The Alpha Legal Foundation, which works to increase the number of underrepresented attorneys in Maine’s top positions of legal leadership and scholarship

- Chauncia Willis, Co-Founder and CEO of the Institute for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Management (I-DIEM)

- Jacqueline Patterson, Founder and Executive Director of The Chisholm Legacy Project: A Resource Hub for Black Frontline Climate Justice Leadership

- Dr. Atyia Martin, CEO and Founder of All Aces, Inc. and author of We Are the Question + the Answer: Break the Collective Habit of Racism + Build Resilience for Racial Equity in Ourselves and Our Organizations

- Monica Sanders, Founder of The Undivide Project and Professor of Law, Policy and Practice in Disasters and Complex Emergencies at the Georgetown University Law Center

- Dr. Anelle B. Primm, Senior Medical Director of The Steve Fund, Senior Psychiatrist Advisor at Hope Health Systems, Inc., and Co-Convener for the Oculus Mental Health Alliance

- Leslie Luke, Curtis Brown, Yolanda Jackson, Bobby McCane, and all of those serving in climate-related emergency management

Lighting a Lamp for Future Generations

Climate change is an overwhelming challenge for all of us, but there’s hope in the tenacity of those already making a difference.

Director Coleman recalled an interaction with a pastor during a food drive for victims of Hurricane Ida that fueled his optimism. “It was the conversations that I had, both with that pastor and some of the community leaders and advocates and that sense of relief, but humble understanding that it was just the beginning of a long journey in the survivors that we were able to meet that really continue to give me hope.”

For me, hope is found in the thousands of youth advocates my team and I have engaged with through The Climate Initiative. The increasingly proactive and informed approach we’re seeing from our rising generations, who come from all walks of life, assures me that our planet’s future is in good hands.